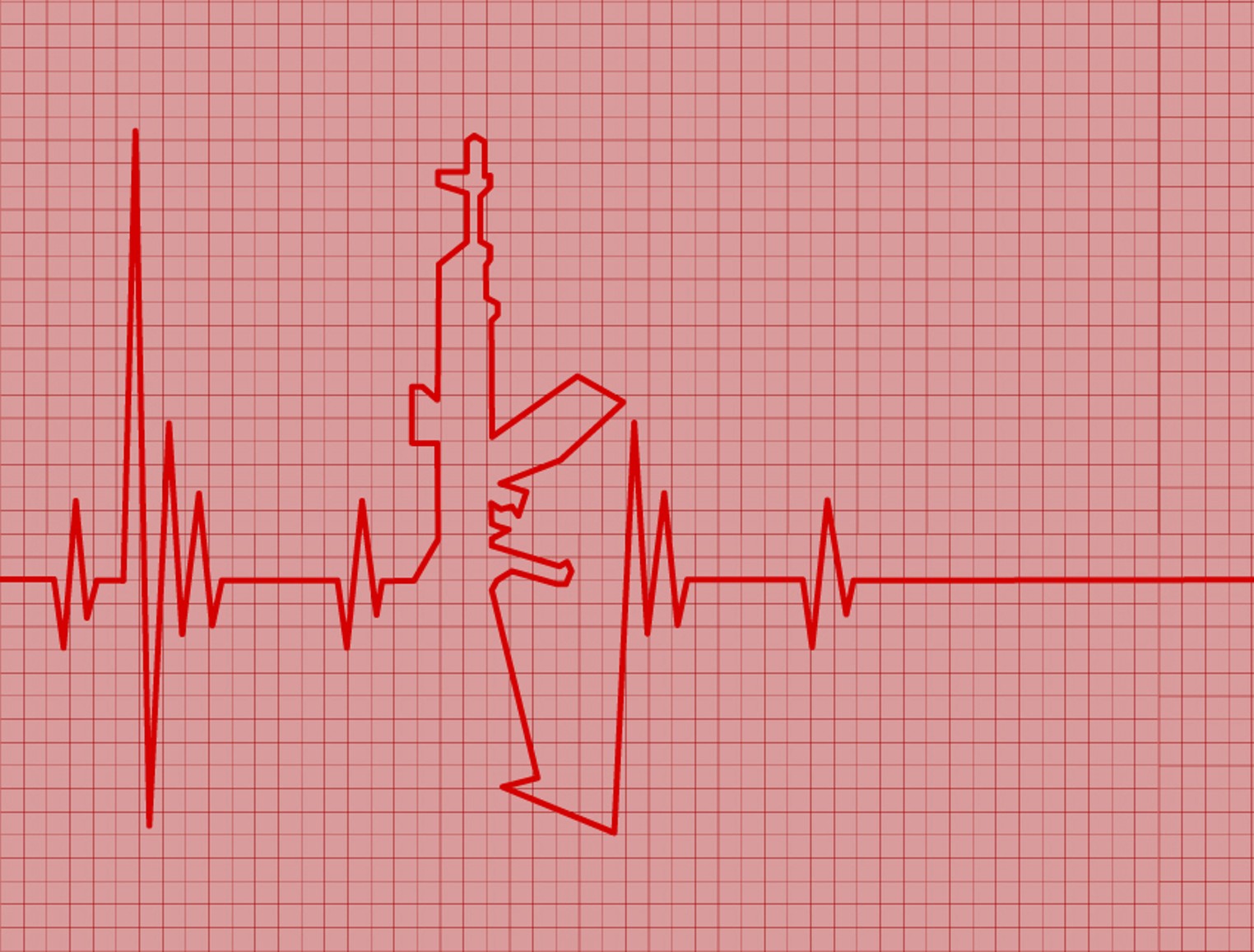

Bill by Dallas Lawmaker Aims To Fix ‘Epidemic’ of Violence Against Healthcare Workers

Last October, a gunman killed two healthcare workers after assaulting his girlfriend, who had just given birth to their baby at Dallas Methodist Hospital. Nestor Hernandez, 30, was out of prison on parole but had reportedly removed his ankle monitor at some point prior to the fatal shooting.

Now, a Dallas lawmaker is proposing legislation aimed at protecting hospital workers and others in the broader community.

Democratic state Rep. Rafael Anchía has introduced two bills to help prevent such a crime from occurring again. House Bill 3547 would prohibit parolees from cutting off their ankle monitors (which is not currently a criminal offense), and HB 3548 would make it a third-degree felony to assault hospital personnel.

The bills are named after the two Methodist hospital employees killed in October’s attack, Jacqueline Pokuaa and Katie “Annette” Flowers.

“Our hospitals need to be safe havens, and our hospital workers need to be protected,” Anchía said during a press conference Monday.

Dallas-Fort Worth Hospital Council President and CEO Stephen Love further highlighted the need for such safeguards during the conference. The Oct. 22 shooting was a “tragedy,” he said, but it’s unfortunately far from an outlier.

Surveys have found that hospitals across the country regularly witness workplace violence, Love said.

“We have to realize that some days, emotions run high,” he continued. “But we need a safe place for the patients, for the patients’ families, and, of course, the healthcare workers.”

Hospitals throughout Texas and the U.S. struggled with workforce shortages during the worst of the coronavirus pandemic. Staffing problems, though, have continued to fester.

Serena Bumpus, CEO of the Texas Nurses Association, cited a 2022 study that found in the second quarter of last year, an average of more than two nursing personnel were assaulted every hour. That’s around 57 assaults per day and nearly 1,740 per month, she said.

In reality, those numbers are even higher because assaults often go unreported by nurses, she said. Many healthcare organizations don’t have a process for addressing or preventing such violence.

“I have been a registered nurse for 20 years,” she said. “Workplace violence has reached epidemic proportions in the last several years, specifically since COVID.”

“If we don’t have nurses taking care of Texans, then our healthcare system will essentially fail.” – Serena Bumpus, CEO of Texas Nurses Association

tweet this

Nurses have told Bumpus stories of people getting held at knifepoint, being repeatedly hit and kicked, and receiving threats from some who say they will return and “shoot up” the facility. Verbal abuse, sexual harassment and sexual assault were also included in these reports, she said.

Nursing shortages have prompted nearly two-thirds of the state’s hospitals to experience a reduction in beds and services, according to a recent survey by the Texas Hospital Association. In addition, 98% of survey respondents said that violence toward hospital workers has either remained the same or significantly spiked since the beginning of the pandemic, with 61% reporting that the severity of the violence has worsened.

Just one out of the survey’s 178 participants said that the frequency of violence has decreased since COVID-19.

“If our staff isn’t safe and they’re not wanting to come back to work, it’s a major issue for the hospital in general and its livelihood,” Cameron Duncan, THA’s vice president of advocacy and public policy, told the Observer. “So basically, anything we can do to keep them safe, and we’re happy to support those bills … out there that do that.”

Anchía’s bill aimed at tackling hospital-worker assault is a “good part of the strategy to prevent workplace violence,” Duncan said. He also pointed to another proposal, HB 112, that would require hospitals and other healthcare facilities to roll out workplace violence prevention policies and lead to standardization.

Dr. Sue Bornstein, chair of the Board of Regents of the American College of Physicians, noted via email that Congress last year considered the so-called SAVE Act, which partly called for enhanced penalties for attacks in hospitals.

On a national level, healthcare workers are five times more likely than other employees to endure workplace violence, the Association of American Medical Colleges reported in August. And between 2011 and 2018, the rate of injuries sustained from such attacks increased by 63%.

Some hospital systems are now restricting building access for visitors, “flagging” the records of anyone who lashes out at employees and training staff in de-escalation techniques and violence prevention, Bornstein said.

“It’s a sad commentary on our society that hospitals whose purpose is to heal are also places of violence,” she said, adding that Anchía’s proposed legislation is a “step in the right direction to make these institutions safer for patients and professionals alike.”

Everyone in the community has been or will be touched by a nurse at some point in their lives, Bumpus said, but workplace violence is leading some to flee the field.

“If we don’t have nurses taking care of Texans, then our healthcare system will essentially fail,” she said. “I encourage the public to also advocate for the prioritization of workplace violence prevention in our healthcare facilities so we can continue to keep nurses within the profession and at the bedside.”

[ad_2]

Share this news on your Fb,Twitter and Whatsapp

Times News Network:Latest News Headlines

Times News Network||Health||New York||USA News||Technology||World News