Meet the American who fought and bled at the Alamo but lived to tell its heroic tale: Slave Joe

The Battle of the Alamo holds a heroic place in American lore, nearly 200 years after its defenders were slaughtered by bullets and bayonets.

“The garrison are to be put to the sword, if the fort is taken,” Alamo co-commander Lt. Col. William Barrett Travis, just 26, wrote in a combative statement of Texan defiance on Feb. 24, 1836, as the Mexican army began a two-week siege of the former Spanish mission.

“I shall never surrender or retreat,” the defender vowed.

Travis was savagely killed at the Alamo, along with 188 other patriots in the cause of Texas independence. General Santa Anna’s vastly superior force overran the fort on March 6.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO INVENTED THE ZIPPER, ONE OF THE WORLD’S MOST USEFUL DEVICES: WHITCOMB JUDSON

Americans remember the horrifying tale of Travis and the Alamo defenders today largely because of one man.

His name is Joe. He was a slave.

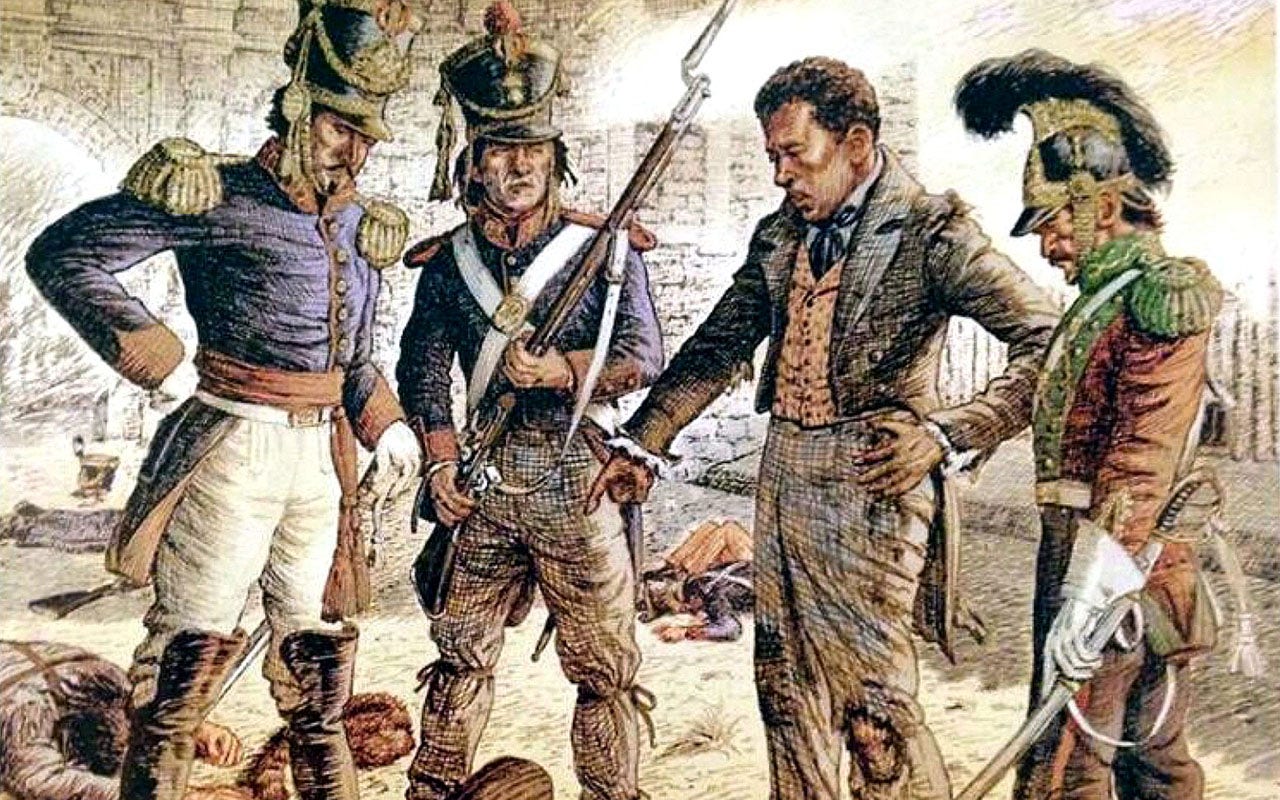

Slave Joe, suffering from bullet and bayonet wounds, was forced by Santa Anna’s men to identify the bodies of defenders of the Alamo, March 6, 1836. Illustration by Gary Zaboly. (Illustration by Gary Zaboly, used with permission)

Slave Joe fought and bled and nearly died with Travis, Jim Bowie and Davy Crockett inside the walls of Alamo.

He fought for freedom while living in bondage. He miraculously lived to tell the world the heroic tale.

“Joe gave us the traditional story of the Alamo that generations of Texans have learned over the years.” — Alamo curator Ernesto Rodriguez

“Joe is the one who gave us the traditional story of the Alamo that generations of Texans have learned over the years,” Ernesto Rodriguez, senior curator and historian for the Alamo, told Fox News Digital.

Texas lost the battle — but it won the war.

Texas delegates, with equal defiance, declared independence from Mexico just four days before the fall of the Alamo in the settlement of Washington-on-the-Brazos.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO TAUGHT THE TUSKEGEE AIRMEN TO FLY: PIONEER PILOT CHARLES ‘CHIEF’ ANDERSON

Stirred by Joe’s heroic story of bravery in the face of death — “Remember the Alamo!” — inspired Texans crushed Mexican forces just a few weeks later in the Battle of San Jacinto.

The Republic of Texas was now a free and independent nation, soon to become one of the United States.

Its honor as the Lone Star State is not just as a nickname; it was a powerful statement of national identity. The proud heritage was written by the blood of the men that spilled on the ground of the Alamo in 1836.

Lee Spencer White, left, and Ron J. Jackson Jr. are the authors of the 2015 book, “Joe, the Slave Who Became an Alamo Legend.” It tells the remarkable tale of the slave who fought and bled at the Alamo and lived to share the heroic tale for posterity. (Courtesy Lee Spencer White and Ron J. Jackson Jr. )

Americans have remembered the Alamo. They forgot about Joe.

Two authors have spent decades looking for him, telling his tale.

“Joe is like a member of our family, and our biggest goal has always been to find his actual family,” historian Lee Spencer White told Fox News Digital.

“He slipped through the cracks of history.”

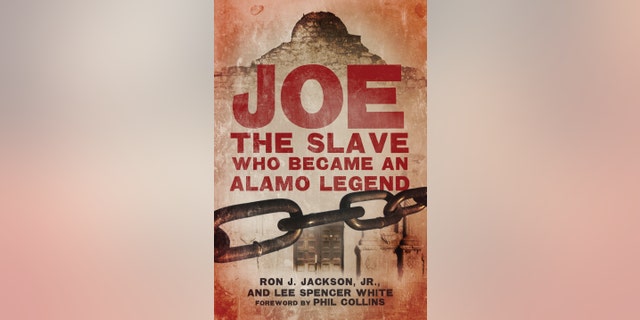

She wrote “Joe, the Slave Who Became an Alamo Legend” with co-author Ron J. Jackson Jr. in 2015. Based in Texas, she’s also the founder and president of the Alamo Defenders Descendants Association.

She’s haunted by the image of Slave Joe, rifle in his hand, looking at the giant force arrayed against the Alamo’s tiny band of brothers, expecting certain death.

“In a dark moment like that, we all wonder, ‘Would I stand and fight, or would I flee and live another day?” White asked.

Slave Joe stood and fought.

Born with storytelling in his blood

Joe was born on an unknown date in 1815 in Mount Sterling, Kentucky, near Lexington, on the farm of Dr. John Young, according to Blackpast.org, a repository of African American history.

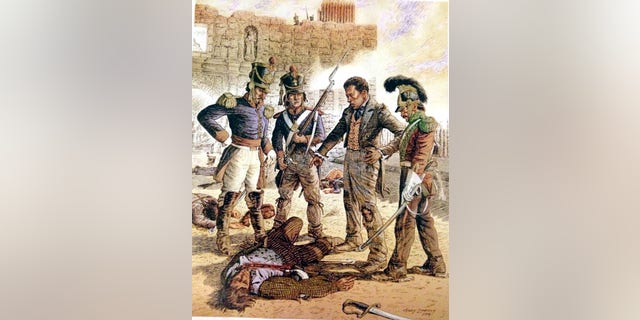

Slave Joe became a fugitive after the Battle of the Alamo. He fled Texas in 1838 to find the family of master William B. Travis, who was killed at the Alamo, in Alabama. Lee Spencer White and Ron J. Jackson Jr., authors of “Joe, the Slave Who Became an Alamo Legend,” traced Joe’s life to Alabama but never learned his fate. Illustration by Gary Zaboly. (Gary Zaboly illustration, used with permission)

“Young founded the town of Marthasville, Missouri, where Joe spent his childhood and adolescence as a field worker,” the site reports.

He and his mother, sister and brother William ended up as the property of Connecticut businessman Isaac Mansfield, who brought the family to St. Louis around 1829.

Slave Joe was owned by four different masters in his life, according to White and Jackson.

“Joe is like a member of our family, and our biggest goal has always been to find his family.” — Author Lee Spencer White

He was sold to William B. Travis — the same exact Travis of Alamo fame — in 1834 and separated from his family. Travis spent $410 for Joe — for another human being.

Joe’s older brother William escaped bondage about the same time and made his way to Boston.

The two brothers apparently never saw each other again, nor knew each other’s fate.

Authors Jackson and White made a remarkable discovery in their search for Joe. As they scoured records, they discovered the story of William Wells Brown, a prominent Boston abolitionist and author.

William Wells Brown was an escaped slave who became a distinguished abolitionist and author in Boston, widely considered the first African American novelist. He was raised in slavery with his brother Joe, an enslaved survivor of the Alamo who recounted its heroic tale to Texas officials. (Image courtesy The University of Oklahoma Libraries, Western History Collections)

He is considered by many the first major African American writer. His 1853 novel of slavery, “Clotel,” is believed to be the first novel published by a Black author in U.S. history.

Brown and Slave Joe were brothers. They shared the same mother — and were born a year apart on the same farm in Mount Sterling to different fathers.

Brown, through his father, was a direct descendant of Mayflower Pilgrim Stephen Hopkins.

Truth is more remarkable fiction, as storytellers often note.

Joe, it turns out, had storytelling in his blood.

Shoulder to shoulder by folly of fate

Davy Crockett was the most famous of the Alamo defenders. He spent eight years as a U.S. congressman from Tennessee before moving to Texas and dying a freedom fighter.

He was the exception among Alamo defenders. They were largely “common men,” noted White.

William B. Travis, 26 years old, was co-commander of the defense of the Alamo. He was killed during the collapse of the defense on March 6, 1836. Travis’s slave, Joe, fought beside him and survived, giving the world its best-known account of the famous battle. Illustration by Gary Zaboly. (Gary Zaboly illustration used with permission)

They were haberdashers, shopkeepers and teamsters. There were six doctors and six lawyers among them. They were mostly young: average age 26, the author said.

Joe was 20 or 21 years old.

“Alamo defenders hailed from 18 U.S. states and six different nations – seven if you count an independent Republic of Texas.”

The men who died at the Alamo nearly 200 years ago represented the incredible diversity of the American people. They hailed from 18 U.S. states and six different nations — seven if you count an independent Republic of Texas.

The heroes of the Alamo were German, Irish, English, Mexican, Mestizo, Native American, European and African.

They were American.

“Joe, the Slave Who Became an Alamo Legend” was written by Lee Spencer White and Ron J. Jackson Jr. It was published in 2015. (University of Oklahoma Press)

“By folly of fate, they found themselves standing shoulder to shoulder … ready to die in defense of freedom and independence,” Jackson and White write in “Joe, the Slave Who Became an Alamo Legend.”

The Mexican force standing outside the walls of the Alamo ranged from 1,500 to 6,000 men, according to various sources. They made their final assault on the morning of March 6.

They quickly overran the fort, rummaging through each room to find the last holdouts.

Engraving of the siege of the Alamo, the first 13 days of the Battle of the Alamo, from the book, “Brief history of Texas from its earliest settlement to which is appended the constitution of the state,” by De Witt Clinton Baker, 1873. Courtesy Internet Archive. (Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images)

Pioneer and knife namesake James Bowie died with loaded pistols in each hand: “A frenzy of bayonets pierced his body until a lead ball struck him in the head, splattering his blood and brains against the wall,” write Jackson and White.

Joe watched the final moments of the carnage “through the thick blue haze of smoke … muscles strained from tense grip on his loaded gun. Survival looked bleak.”

“A frenzy of bayonets pierced Bowie until a lead ball struck him in the head, splattering his blood and brains against the wall.” — Jackson and White

He was shot in the side by one Mexican solider while another lunged at him with a bayonet. A Mexican officer spared Joe seconds before he might have been slaughtered.

The slave, to his own surprise, was arrested instead.

“Mangled and mutilated bodies littered the Alamo courtyard” as Joe was led outside, the authors write. “Clumps of dead Mexican soldiers here, bloodied and lifeless Texans there.”

Those Texans still with breath in their lungs were killed instantly. The Mexicans gathered and torched the bodies.

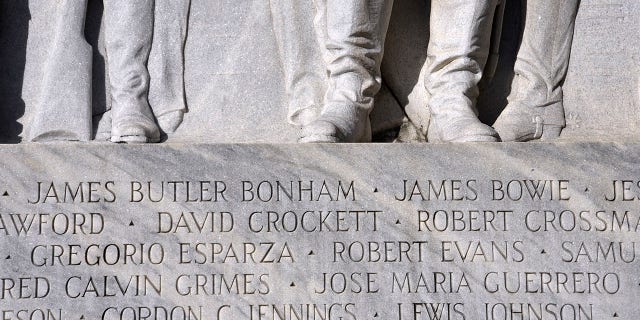

Legendary frontiersman David Crockett is among the men whose names and likenesses are included on the Alamo Cenotaph monument near Mission San Antonio de Valero, better known as the Alamo, in San Antonio, Texas. The granite and marble monument, erected in 1939, honors the men, including Davy Crockett, who died in the famous Battle of the Alamo in 1836. (Robert Alexander/Getty Images)

“Ghostly faces of the dead peered from the flames as the putrid odor of burning flesh and hair permeated the air. Joe undoubtedly witnessed the ghastly scene in horror.”

Joe was soon interrogated by Santa Anna himself. The Mexican dictator reportedly sneered when Joe said more U.S soldiers were expected to arrive and fight alongside the Texans.

“Satisfied that Joe was of no more use to him, Santa Anna abruptly dismissed the slave from his presence and ordered him taken away by guards,” Jackson and White report.

“By the next day, perhaps before sunrise, Joe had successfully escaped the Mexican guard. He quietly slipped out of town and ventured into the open prairie.”

A painting depicting the final hours of the Battle of the Alamo with former congressman and frontiersman Davey Crocket in the foreground on March 6, 1836, in San Antonio, Republic of Texas. (Illustration by Ed Vebell/Getty Images)

Joe, along with Susanna Dickson, a female survivor of the Alamo, and her child, found a group of Texas scouts days later.

They shared their tale first with Texas revolutionary leader Sam Houston. Joe then arrived in Washington-on-the-Brazos on March 20 — already a celebrity — to tell the story of the Alamo to the delegates who declared independence from Mexico four days before the slaughter.

“Officers and soldiers alike gathered around Joe to hear the haunting details he provided. Bowie? Dead. Travis? Shot in the head on the north wall. Crockett? Also died heroically.”

“The servant of the late lamented Travis, Joe, a black boy of about 21 or 22 years of age, is now here,” Texas historian William Fairfax Gray wrote in his diary from Washington-on-the-Brazos.

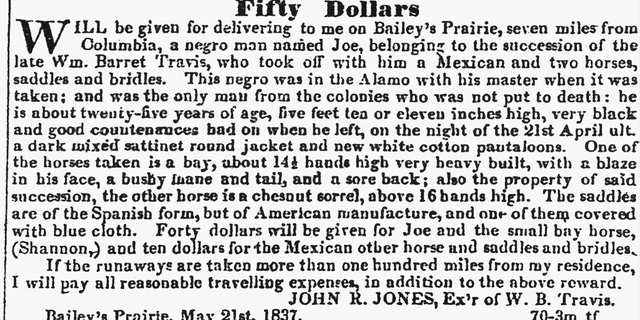

A reward of $50 was offered in a newspaper ad for Slave Joe, despite his heroics after the Battle of the Alamo. (Ronald J. Jackson Jr. and Lee Spencer White)

“He was in the Alamo when the fatal attack was made. He is the only male, of all who were in the fort, who escaped death, and he, according to his own account, escaped narrowly.”

Slave Joe, a Black man who had never known freedom, gave birth to a legendary tale of defense in the name of liberty.

Joe’s tale for a new generation

Slave Joe made his way to Alabama in the years afterward to find the Travis family.

He revisited the Alamo with James Travis — the brother of the Alamo hero — sometime around 1900, according to records that Jackson and White found.

A tourist uses her phone and relaxes with her dogs in front of Mission San Antonio de Valero, better known as the Alamo, on Dec. 9, 2018. The former Franciscan mission was the site of the Battle of the Alamo in 1836 during Texas’ war for independence from Mexico; Texan defenders were defeated by Mexican troops under General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. (Robert Alexander/Getty Images)

He was an elderly man of 85 years old at the time. T

he known story of Joe’s life ends there.

“In all likelihood he’s buried on the old Travis plantation” near Evergreen, Alabama, said Jackson.

Slave Joe, a Black man who had never known freedom, gave birth to a legendary tale of defense in the name of liberty.

Nobody knows for sure.

Other defenders of the Alamo have been remembered as great heroes in an epic American story — honored with poetry and prose, monuments and marble, for nearly 200 years.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO FIRST RECORDED THE BLUES, NATION’S ORIGINAL POP DIVA MAMIE SMITH

Slave Joe, the man whose words memorialized those men as heroes, is buried in an unknown spot most likely in an unmarked grave.

Yet the story of the Alamo — Joe’s story of the Alamo — will be remembered for generations.

The Alamo opens a new $20 million Collections Center in March 2023, with plans for a $400 million expansion to be completed by 2026. (Courtesy the Alamo)

“It’s really important that one of the pivotal moments in Texas history was told by someone who didn’t have the same freedoms as everybody else,” said Rodriguez, the Alamo curator and historian, noting that it gives insight into the complexities of the American experience.

The museum opens a new $20 million, 24,000-square-foot Alamo Collections Center on March 3, vastly expanding the artifacts available for public display.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTER

It will be followed by an even more ambitious $400 million Alamo Visitor Center and Museum slated to open in 2026.

The authors, like most Americans, are troubled by the paradox of the Alamo story: Heroes owned slaves, slaves fought for freedom.

Slavery existed in the United States; but it also existed everywhere in the world. In some cases, it still does.

“Life is messy. History is messy. Things are complex.”

Modern nations practiced widespread slavery in Europe and in Asia less than 80 years ago, long after it was eradicated in the United States.

Americans from Texas and all other corners of the nation stormed the beaches of Normandy and Iwo Jima to end it slavery on much of the planet in World War II.

Without the legacy of the Alamo, perhaps Americans wouldn’t have done so.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

“Life is messy. History is messy. Things are complex. Not everything is a 1950s western where you have the good guys and the bad guys,” said Jackson.

“I don’t think any of that takes away from what they did at the Alamo and how they died. They were all heroes. Including Joe,” he said.

To read more stories in this unique “Meet the American Who…” series from Fox News Digital, click here.

Share this news on your Fb,Twitter and Whatsapp

Times News Network:Latest News Headlines

Times News Network||Health||New York||USA News||Technology||World News