History Professor Seeks ‘Truth and Reconciliation’ from the State and the Texas Rangers

She didn’t see the gunshot, but it happened close enough for her to hear.

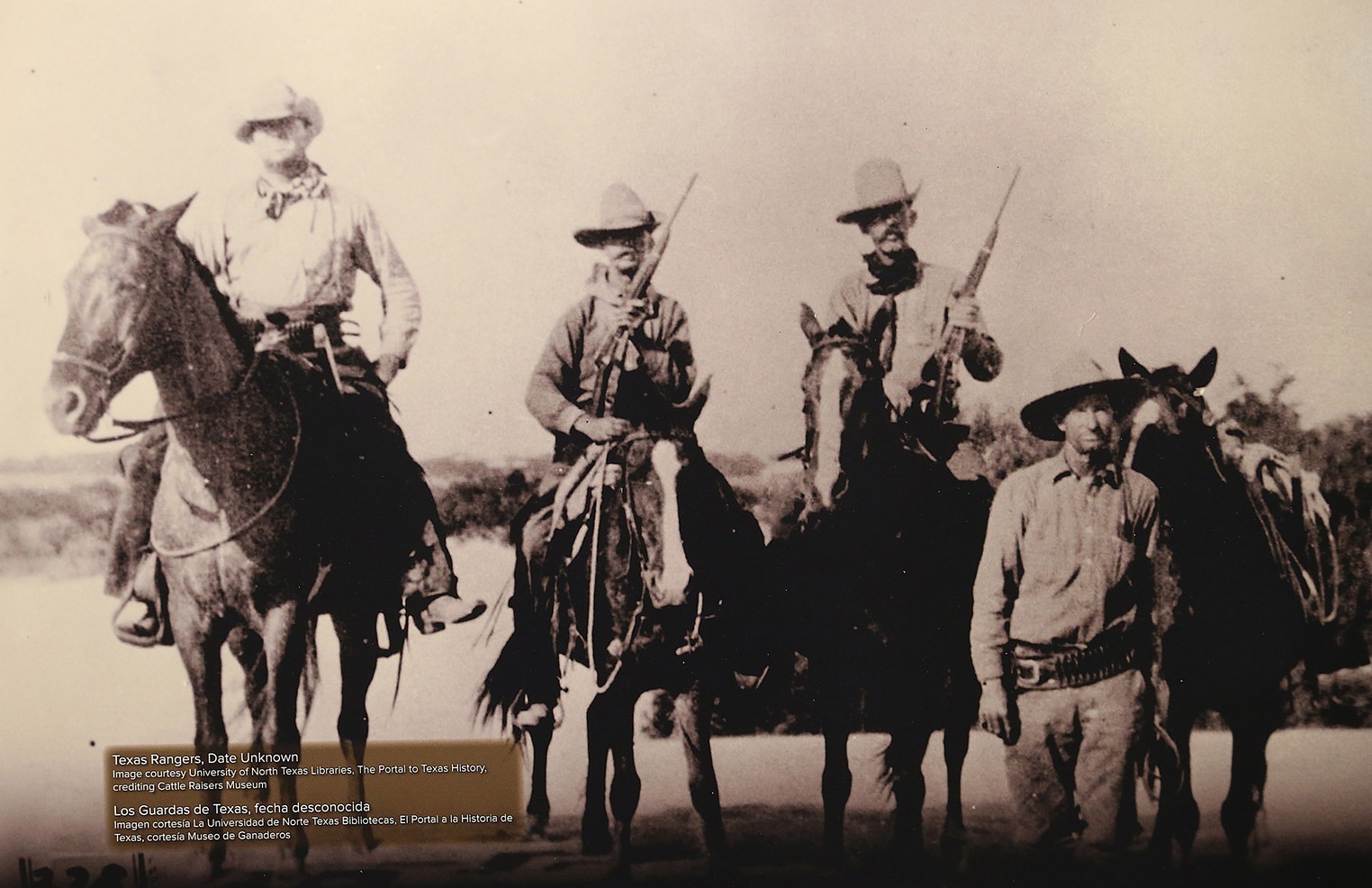

It was 1915, and los rinches — the Texas Rangers — were killing Mexicans, Mexican Americans and hundreds of other people with relative impunity. On this particular day, September 16, members of the widely feared police force were questioning a woman named Santos Gamboa and her family at a ranch near Edinburg, Texas.

“The Rangers were apparently talking to her,” Trinidad Gonzales said of Gamboa, recounting the scene for a Texas Monthly podcast. Then, “they pulled her husband and her father-in-law to the side.”

That’s when the shot rang out.

Growing up, Gonzales heard this story several times. His father would tell him over barbecue, or his mother would tell him over coffee and pan dulce. He would learn, for instance, that his grandmother was 15 months old on the day of the murder, and he learned how Gamboa laid her husband and her father-in-law to rest in a nearby cemetery before starting over. Gamboa would eventually own cattle and a store, and many years later, a young Gonzales would buy candy from that same store. In other words, Gamboa survived as well as she could in the years before and after La Matanza: a decade of anti-Mexican violence perpetrated by men like the Rangers. But like hundreds — maybe thousands — of victims, survivors and family members from the same time period, she never got closure.

Her great-grandson hopes to change that.

On Thursday, February 23, Trinidad Gonzales, a history professor at South Texas College, sent a formal letter to Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, the state’s Speaker of the House and multiple chiefs of staff for politicians in the Rio Grande Valley. The objective of the letter, Gonzales tells the Observer, is to finally begin the healing process for families who, like his own, lost loved ones to the state-sanctioned violence carried out by the Texas Rangers.

“The first thing I think everyone needs to understand is this is an issue of justice,” Gonzales says. The letter puts the ball in Texas’ court. “Are they going to be on the side of justice or injustice? It’s not a left or right issue; it should be bipartisan.”

“The first thing I think everyone needs to understand is this is an issue of justice.” – Trinidad Gonzales

tweet this

Specifically, Gonzales is asking the state to create an investigatory “truth and reconciliation” commission that will, according to his letter, “allow families and communities of Texas to be heard.” Their focus would be the years between 1836 and 1980, during which the Rangers murdered hundreds. According to journalist Doug Swanson’s book Cult of Glory, the fabled law enforcement unit was at one point as feared as the Ku Klux Klan.

Gonzales’ proposed commission would be composed of an equal number of Republicans and Democrats, and they would hold meetings in five different Texas communities, gathering records and testimony from experts, families and even Ranger supporters eager to point out the force’s heroics.

“I want them to be a part of this conversation,” Gonzales says of the pro-Ranger contingent. “That’s part of due process.”

When the hearings were finished, the commission would make their findings public, then propose recommendations such as historical markers, public memorials and an official apology.

Gonzales himself doesn’t exactly know what he wants.

“I know I want an apology, but I don’t have all the answers yet,” he recently told the Observer.

What’s important, he says, is that the state of Texas makes an effort to investigate the Rangers’ human rights offenses.

South Africa created such a commission to investigate apartheid, and similar bodies have been implemented in Rwanda and Guatemala.

Gonzales, a former journalist, first thought of the idea in late 2021, at which point he resigned from the board of Refusing to Forget, a nonprofit focused on the Rangers’ legacy of violence. He didn’t want to serve on the board while pursuing this commission, he says, because it could be seen as a distraction.

He is also aware his request for a commission will likely be politicized. After all, this is the same lieutenant governor who effectively barred a museum from hosting an event critical of the mythology surrounding the Battle of the Alamo.

That’s why Gonzales’ letter includes a word one might not expect to see in a document discussing century-old violence: “woke.”

“I make this request as a matter of justice,” he writes, “not some WOKE ideology. The need for justice dates before the idea of WOKENESS even was conceived.”

Indeed, descendants of Ranger victims have been calling for justice for decades, and Gonzales’ letter cites a 1929 newspaper editorial lamenting the impunity with which the heroes of Texas lore committed mass atrocities. Gonzales also includes the names of many victims, including those killed in the infamous Porvenir Massacre.

“As far as the state is concerned, these people are still alive,” he says, noting that the families have never received a death certificate. Even a seemingly small act like that, he says, can go a long way to providing closure. That’s why people like his great-grandmother bury their dead in cemeteries: to remember.

“It’s human nature, going back thousands of years, to name the people we’ve lost,” Gonzales says. “There’s a dignity in being remembered.”

[ad_2]

Share this news on your Fb,Twitter and Whatsapp

Times News Network:Latest News Headlines

Times News Network||Health||New York||USA News||Technology||World News